Ohjaus:

James TobackKäsikirjoitus:

James TobackKuvaus:

Michael ChapmanNäyttelijät:

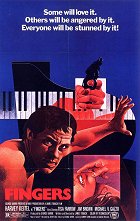

Harvey Keitel, Tisa Farrow, Jim Brown, Michael V. Gazzo, Marian Seldes, Danny Aiello, Ed Marinaro, Tanya Roberts, Tony Sirico, Dominic Chianese (lisää)Juonikuvaukset(1)

Harvey Keitel plays a piano virtuoso with a twisted second job - he's the muscle man who 'collects' on his mob father's debts. Of course, this creates an internal struggle between the artist's commitments to his father and his love of music. (jakelijan virallinen teksti)

Videot (1)

Arvostelut (1)

The first and evidently best directorial work of the erstwhile film critic James Toback somewhat belatedly follows on from the cycle of New Hollywood “de-heroisation” dramas (e.g. Five Easy Pieces, Taxi Driver, Night Moves). Above all else, Jimmy is no hero. He has no goal, he doesn’t command respect among men, and women find him laughable. He has to force sex on his partner and, because of his premature ejaculation and prostate problem, intercourse is a bad dream (as Carol rightly calls his post-coital state). He doesn’t live for action; he lives for obsession. His obsession with finding his place in the world is slowly destroying him instead of leading him to a satisfying awakening. By performing the final act of castration, not just in a figurative sense, he may become a man (or an animal?), but what remains for him to live for? (There are numerous possibilities for psychoanalytical interpretation given the involvement of the characters of the cold mother and father, a partner rather than a rival, which frustrates Jimmy because he has no one to compete with him.) His neurotic behaviour, outwardly manifested by tapping along with the constantly playing music, reveals his mental instability. At the same time, he finds his equilibrium only in music. He has control over his own body only when he plays the piano and (in contrast to Bach, which creates the impression of the protagonist’s torn nature) the pop songs in which he ceaselessly immerses himself expand his paltry personal space. Unlike in standard Hollywood films, we are faced with an unreadable person and the director does not help us to “decipher” him. The camera follows Jimmy from a distance, in long, unchanging shots that are indifferent to the viewer’s desire to see more and be able to form a picture from multiple segments. There are no certainties in the form of establishing shots or exchanges of dialogue using the shot/counter-shot technique, disruptive elements enter the mis-en-scéne (the little girl in the scene with the cop) and, for those who would still not be uncomfortable enough, Michael Chapman prepared some expressionistically skewed camera angles. Jimmy’s loss of control over his own identity (and possibly over perceived reality – the contentious scene with the potent black man could easily be his dysfunctional erotic fantasy) is reflected in the directorial loss of control over the final structure of the film, which may be a sign of filmmaking courage, just as it could be an alibi for the shortcomings of a directorial debut. However, Keitel’s work with his fingers is flawless. 75%

()