Ohjaus:

Paul SchraderKuvaus:

Bobby ByrneSävellys:

Jack NitzscheNäyttelijät:

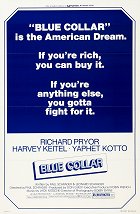

Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel, Yaphet Kotto, Ed Begley Jr., Harry Bellaver, George Memmoli, Lucy Saroyan, Lane Smith, Cliff De Young, Tracey Walter (lisää)Juonikuvaukset(1)

Three auto assembly line workers, fed up with union brass and tired of scraping by, hatch a plan to rob a safe at union headquarters. Disappointed with their measly bounty, they realize they've made off with something much more valuable than cash. Their unexpected swipe suddenly envelopes the three autoworkers in a desperate fight against corruption and organized crime. (jakelijan virallinen teksti)

(lisää)Arvostelut (1)

Blue-collar worker – a member of the working class who strives to make a living off manual labour. There is no fearless (black) hero spending his nights planning the heist of the century. If anything, he will want to earn money for himself, not change the way things are. Blue Collar is neither blaxploitation nor a heist movie, whose genre simplifications Paul Schrader rejects in his directorial debut. The crime dimension was suppressed in favour of the social dimension. Schrader is interested in the ordinary worker providing for his family and whose main enemies are the people in charge and whose main allies should be the labour unions. That is, in an ideal society. Not in American society at the end of the crisis-ridden (Watergate, oil embargo, Vietnam syndrome) 1970s, when few trusted those who stood above them. The production lines must not stop, regardless of the victims of the system. Uncle Sam would not like that. The trio of friends from Detroit, Motor City, slowly come to the realisation that the government (ordinary people in charge) is not supporting them. That’s an obvious fact today, but it was a relatively fresh discovery at that time. Together with Taxi Driver (for which Schrader wrote the screenplay), this film ranks among the darkest works that the new generation of Hollywood filmmakers served up back then. People corrupted, society plundered. Money and power endure more than friendship. Schrader directs without any pathos. He doesn’t use music and he doesn’t judge. He shows. He doesn’t explain the details. He doesn’t have to. In order for us to understand, it’s enough that he familiarises us with the situation of the characters, who are of greater interest to him than the action (which is aided by the solid acting of Keitel and Kotto, as well as the atypically non-comedic Pryor). Schrader leaves open spaces between the scenes, so that one is not closely tied to another. It’s as if what happens between them is out of his control and inevitable. A genre film would not have allowed such under-tightening of the screws and would have promptly offered an answer to every question. Schrader, however, is very well aware of the difficulty of finding the right answers. 80%

()