Arvostelut (536)

Olen utelias - sininen (1968)

The second part exploits the boundary between fiction and reality, but this time using different techniques: instead of sociological research and a documentary objective detachment from the protagonists, it emphasizes the personal aspect of the protagonist’s personality, which is also connected with the emphasis on a "more traditional" metafictional approach, thus subverting the uniqueness of the fictional character by showing its secondary nature in relation to the film's creator. Compared to the first part, the second part is more visceral, and moreover, it is also gloomier and bleaker (after all, it is melancholic blue compared to the cheerful yellow): the search for oneself from the perspective of the protagonist and her exploration of her place in contemporary society cannot be carefree because it concerns the establishment of identity in an uncertain world. Fortunately, it is uncertain - freedom, which is always open, proclaims its anxious share. Otherwise, the second part is in no way just a continuation of the first part, as it differs not only formally but also in terms of content, and in the second case in that the "events" of the second part often precede the events of the first part and in a way "anchor" it. However, that is a strong word because here too the viewer is confronted with the necessity of acknowledging the non-reconstructability of the difference between the fictional plot and the alienating splitting, which turns the main character into an actress or the director into an actor, intervening in the world of fiction and what is "real" (the one that controls fiction). The viewer thus gets used to the permeability of both instances, thanks to which reality also serves fiction in its artistic effect.

Sud dolžen prodolžaťsja (1930)

A feminist educational film, which shows the greatness and tragedy of Soviet cinema at that time. Without a doubt, there is nothing to criticize here in terms of the content of the deserving and progressive theme of the struggle of a wife-employee from the electrical plant for recognition of her right to work (by this I mean emancipation from the "natural" sphere of "women's" self-realization). The question of women's emancipation was raised in the USSR in the 1920s - thanks also to that abominable "totalitarian" always criminal ideology that ruled there at that time... - as a problem for an accelerated/"revolutionary" solution. We can also state that, compared to the West, there were often more discussions about such "feminist" issues in public discourse. So, wherein lies the tragedy? In the fact that the main protagonist’s struggle, during which she exposes both her husband and high-ranking people as advocates of surviving bourgeois sexist views, will soon become the norm for Stalinist purges and denunciations – yet now, they are of a political nature. /// The fact that Dzigan managed the formal aspects of the matter very well - his sense of composition of large units, also filmed in the studio, or dynamic editing (which, although not reaching the sophistication of the classics of the montage school, is nevertheless aesthetically impressive) - is also worth noting.

A and B in Ontario (1984)

The film was shot in the 60s but not completed until 1984, which coincides with H. Frampton's death. The entire film takes place between two camera perspectives: that of A) J. Wieland and B) H. Frampton. These two are both the subject and the creators, the subject-substance of the film. Thanks to their mutual effort to film each other during their own filmmaking/cinematography work, an image of themselves and the image of the city of Ontario gradually emerged. This fact is characteristic: all the other film cameras in all other films progress in a similar manner, despite the absence of such an obvious splitting that I witness here. Each camera primarily records itself and only secondarily the world/what it wants to depict because it always destroys the world and shapes it according to its own nature (referring to both the technical aspect and the artistic intentions of the director and cameraman, etc.). A and B in Ontario is a material demonstration of this.

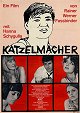

Katzelmacher (1969)

The perfect mastery of a not very commonly used cinematographic procedure - film combinatorics. Fassbinder completely deconstructed the film world into a series of individual elements: constantly recurring locations, within whose boundaries the precise behavior of the film characters unfolds. The film itself is created precisely by combining these elements - the regularity of sequences and expectations are deliberately built up in the first half to be restructured into a slightly different pattern with the arrival of an unknown element, a foreign migrant worker, and thus the very skeleton of the film process stands out. Given that the essence of the plot changes are not changes in the characters' personalities (except for one), but rather their relocation from one predefined location to another, i.e., again a form of combinatorics, although not in space (but let us not forget, as we have seen, that space defines the characters' actions, so it is an integral component of the story), but rather personal (especially the mutual cheating by the couples - their changes in partners substitute for the immutability and stereotyping of their lives).

For Ever Mozart (1996)

A very "plot-driven" (and therefore more accessible to the majority of viewers) film by Godard. Formal techniques are not (unfortunately) utilized as an additional layer of meaning, but rather as a stylistic element - primarily the traditional disjunction of sound and image (an interesting aspect is the absence of classic intertitles). The contrast between the use of classical or classicist (beautiful/kitschy - according to each comrade's taste) beauty in Mozart's music and shots of the seaside, and the horrors of the Yugoslav war, is not as groundbreaking as one might expect. A similar, yet more interesting, juxtaposition can be seen on the content level, where several plot lines intertwine with reflections on the function of art. And art fails in the face of tanks and consumerist viewers, in the hands of the young and the old. Here, as is latent throughout the entire film, a certain painful nostalgia and pessimism are most strongly felt - the young die radically and bravely, but unnecessarily, unable to create anything truly new (in fact, they only reproduce de Musset and Camus), while the elderly director continues to create but cannot reach the superficial external world, which watches the new Terminator in theaters against the backdrop of artillery shells. I am not sure if it's just a correlation or a real causality, but the director's films, in which the aging, unsuccessful, and mocked director is played by Godard himself, playing himself through his own eyes, are better than this one, where he allowed himself to be replaced by an actor.

Glissando (1982)

The film does not use any specific expressive means to communicate with the viewer in a privileged manner but instead addresses the viewer as a whole. If no single approach (the plot, the blurring of the boundaries between dream and reality in the main character, allegory of fascism through social institutions, etc.) can dominate the others, "only" the whole remains - the all-pervading atmosphere. The atmosphere of the film perfectly imitates a slowly decaying, vain, self-destructive, unnecessary fascist society on the brink of war. Just as the atmosphere gradually penetrates each cinematic shot, from the more "realistic" ones to the delirious ones, so too does the stagnant, putrid hospital water gradually seep out into the world - casinos, streets... The significance of the work lies in the fact that the viewer, often "not understanding" the specific events and necessarily being uncertain about the many symbols that Daneliuc places on the film screen, understands the same events thanks to the atmosphere they emit and through which they connect (and retroactively strengthen) with the film as a whole.

Freak Orlando (1981)

It is a film according to the classification table, where the "x" axis and the "y" axis allow for basic coordination of objects within each column - but nothing more. Each column then represents a separate object, "connected" to others not by an internal relationship, but by mere correlation to the basic coordinates. The relation to the "x" axis could be a shift in time and to the "y" axis, the degree of nonsense. The problem is clear – the almost absolute discontinuity between individual objects/scenes, singular images and singular allegories, which is a problem because, for example, an allegory cannot be unique if it is to have a broader significance. In other words, if the thread is lost, all that remains is the panopticon. Ottinger also has a relative aversion to words as a means of communication, not only for the film characters but especially toward the viewer and therefore, trying to extract meaning from technically almost silent Dadaist situations and scenes requires a considerable amount of imagination. However, some scenes are worth it (although I do not know what exactly "it" is...) because you definitely do not see experimental feminist absurd avant-garde every day.

In Gefahr und größter Not bringt der Mittelweg den Tod (1974)

Kluge (together with Reitz this time) once again uniquely colonizes the blank spaces on the map of cinema, settling in its "gaps" and launching an attack on film narration from this unexpected place. Or it is another successful attempt by Kluge to dismantle the false division of cinema into "fiction" and "documentary," "story," and "truth." This is best manifested to the audience in poetic passages, where we observe a "fictional" character wandering through "real" situations from the life of a Western metropolis, accompanied by non-diegetic music. The techniques of cinéma-vérité documentaries blend with fictional narration into a single entity. This entity combines a typified sociological event with the impact and closeness of the individual story of a "living" character, a character with a name. It is obvious that by doing so, the authors achieve a greater effect on the viewer than either a purely "documentary" or purely "novelistic" storytelling method could achieve.

High School (1968)

One year after the creation of this film, the famous philosopher and Marxist Louis Althusser published his most well-known essay, "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses," in France - and it does not take a genius to guess that the main ideological apparatus of modern times appeared to him to be none other than the school. A space of constantly circulating and seemingly imperceptible relationships of discipline, dominance, internalization of external norms, the fabrication of standardized "individuals" in the likeness of writing courses on typewriters - that is, individuals with only one form of communication; in the likeness of fashion courses for girls - that is, with only one form of self-presentation; in the likeness of lectures on sex education - that is, with only one form of intimacy. It is also necessary to remind some of the politically naïve people among us who imagine ideology as a centralized process of deformation led by evil priests (18th century) or totalitarian Nazi-Communists (20th century), that ideology is common to all social formations and serves as a kind of coordinate system in the likeness of cultural patterns - it also serves as orientation in the world and the self-regulation of society, and thus it is spread throughout the fabric of society and necessarily acquired by those who propagate it. Wiseman perfectly shows us this in the final scene with the teacher, who is moved by a letter from a former student who voluntarily went to Vietnam to fight for the safety of a free world. In Wiseman's film, the school is depicted as a self-affirming ideological mechanism of Western (capitalist) society in the late 1960s.

Mandara (1971)

Jissoji developed - this time (mostly) in color - many themes from his earlier film This Passing Life, primarily the themes of desire, religion, death, individual nihilism, the impossibility (?) of community, and human dependence. In the film, even more emphatically, the situation of alienation of the modern individual is depicted - after all, the opening scenes of the film depicting dependence on sexual gratification are simply evidence of the modern individual's attempt to fill their void or squeeze out the trauma of impossibility (?), the difficulty of a real relationship with others, through sex and erotic desire. It is precisely this that gives a person anchoring and certainty - and it is precisely their mirrored reflection in religion, where the essence of an orgasm is manifested - in the suspension of time, the body opens up to eternity: the climax of God or the orgasm of the body. Then there is also a beautifully suggested transition between the situation of the individual and their attempt to replace a dysfunctional ordinary human community with a new one, based precisely on a nihilistic and alienated understanding of sex and religion in the form of a sect. /// Jissoji's film is characterized by a very distinctive aesthetic aspect, and although I acknowledge a certain self-purposefulness in the expressive language, especially of the camera (but not the change between color and black and white), we must appreciate the sense of composition and inventiveness in the construction of film images.