Arvostelut (840)

François Truffaut l'insoumis (2014) (TV elokuva)

“With (every) other activity, I betray film.” This masterful documentary portrait uses scenes from Truffaut’s films to illustrate almost every event in his life (or rather in his autobiography). But if you accept that the focus of the documentary is on Truffaut’s contradictory personality (an introverted intellectual with uncomfortable views who, for example, didn’t mind leading the filmmaking “revolution” at Cannes) rather than on his work, you will experience a pleasant fifty minutes in the company of Truffaut himself and people who were relatively close to him (as opposed to the absent film critics and historians, who might offer an unbiased perspective). It’s a shame that the documentary’s creators don’t incorporate much unique material from shooting and the filmmaker’s family archive (private letters) or scenes of Truffaut speaking into a more meaningful whole. After the introduction, which promises a chronological journey through his life, there is a shift to the crucial themes of his life and work (children and women), so that instead of continuing to tell his life story, the film goes into greater depth only in describing the kind of person that Truffaut was. The film will thus be appreciated rather by people who have already read something about the most watched director of the New Wave and will thus be able to put the confusingly distributed information into a consistent framework.

Tintin seikkailut: Yksisarvisen salaisuus (2011)

It is no longer necessary for anyone to bother with making a film adaptation of the legendary adventure game Broken Sword – in terms of atmosphere, that’s exactly how I imagined it. The exotic settings, the interconnectedness of the plot with history, the brilliant combination of humour and action. Furthermore, there is some slightly adventurous problem solving (figuring out what to do with what’s currently at hand, finding keys, combining objects). The economically managed narrative without a single unnecessary diversion is fully subordinated to the fluidity of the action, which, after the initial explanation of the context and the express introduction of the protagonist, only continues to build. The objective is clear, the fun can begin. With an average shot length of 4.8 seconds (according to the Cinemetrics website), it may have the fastest editing of any of Spielberg’s films, but compared to other 3D action movies, the shots do not alternate very often. On the contrary, great care is taken to arrange the action in space and to work with multiple plans of action simultaneously. It’s a bit in the spirit of slapstick; Spielberg long ago mastered the art of making the context clear through movement instead of words. The movement, whether vertical (forward) or horizontal (into the past), almost never stops and when, as in the middle of the desert, it seems for a moment that no action will happen, the wild hallucinations of one of the characters appear. In addition, the transitions between scenes are very inventively designed, which contributes to the impression of unprecedented fluidity. The rising action curve reaches its peak in a scene lasting several minutes without a single cut, for which I would not shy away from usin the word “masterful” to describe it. It’s all about having fun, isn’t it? But wasn’t the summation of the entire story in the title sequence intended to be a call to lower the demands on the intricacy and intellectually stimulating nature of the content and, with the fascination of a small child, to mainly enjoy the exciting spectacle? I haven’t had this much fun in a long time. Without feeling guilty about the silliness I was watching. The first time, the second time and the third time. And I have zero doubt that I will enjoy it the fourth time. 90%

The Hateful Eight (2015)

The Hateful Eight is a great Tarantino revival and, after a long time, a film for which I would not regret paying a higher ticket price (though I’d still rather pay more for a screening from a 70 mm print). Faces familiar from Tarantino’s previous films, a return to the intimate “whodunit” concept of Reservoir Dogs (despite the epic establishing shots and imaginative use of spatial partitioning, which best stand out on the big screen), references to its own universe (Red Apple tobacco), division into chapters (which, in addition to rhythmising the narrative, serve to reveal new information and redirect the viewer’s expectations), the non-chronological organisation of the narrative (which doesn’t break up the film, but contributes to its overall integrity), visual and motif references to spaghetti westerns (Jackson stylised as Lee Van Cleef) and John Ford’s westerns, as well as to (slapstick) splatter flicks and Carpenter’s The Thing, variations on narrative formulas from blaxpoitation and samurai films, not individual scenes but almost the whole film based on waiting (ours and the characters’) for something to happen (and when something finally does happen, there is – in the roadshow version – an intermission followed by a flashback with Godard-esque commentary) and whether it turns out at the end that some of the characters were connected to each other by something other than a chain. The constant delaying of action and the use of dialogue to draw out scenes of simple actions, which the aforementioned Godard enjoyed using to test the patience of his viewers (see the magnificently retarded scene from Breathless with Belmondo and Seberg blabbering in a hotel room) make The Hateful Eight a unique film not only in the context of contemporary Hollywood production, which offers viewer satisfaction much more quickly, but also in Tarantino’s filmography. The first half of the film is not just a sadistically long prelude. The director uses various delaying tactics from beginning to end and even lets the characters provocatively point that out (“Let’s slow it down”). Regardless of the large number of identified (self-)references, this is a masterfully written and acted film in which everything elegantly clicks into place in the end; it just intentionally takes longer than would have been necessary, which would seemingly work as well only as a stage play (the film is aware of its theatrical structure and thematises it with gusto). Most of the characters play a certain role and the film derives much of its tension from the characters/viewers not knowing who is pulling which end of the rope. Though basically everyone is a lying bastard (those who aren’t won’t survive long), your sympathies will constantly shift from one character to the next depending on what Tarantino reveals about them. As much as to the detailed distribution of power (consisting not only in who has a loaded gun in their hand, but also in who knows what – see all of Chapter Four), the film owes its dynamism to the fast-paced dialogue, the energetic acting and camera movements (drawing our attention to important motifs), the lighting, the refocusing, the work with the depth (height and width) of the space and the editing (taking into account who is looking at whom and how). Even more than Django Unchained, The Hateful Eight would like to be a political allegory in the style of the subversive counterculture westerns of the 1970s, using not very sensitive means to draw attention to the parallels between racism and capitalism. The literalness of the film’s ideological level (lines like “When niggers are scared, that’s when white folks are safe”, the division of the bar into individual American states) contrasts with the much more subtle means by which Tarantino builds tension, creates an oppressive atmosphere of distrust and communicates essential information about who is an ally or an enemy. Even so, this is a brilliant allegory that offers very disturbing and not entirely unambiguous commentary on a different interpretation of law and justice. Tarantino has made an extremely nihilistic western that successfully creates the atmosphere of an era in which people are united mainly by their hatred of a common enemy. Primarily, however, it abounds with the narrative skill of the best Agatha Christie novels. I believe that, like Christie’s books, The Hateful Eight will only get better over time. 90%

Kysymys elämästä ja kuolemasta (1946)

Thirst for life is equal to thirst for Technicolor. Stairway to Heaven is not only a visually captivating but also carefully thought-out film containing more than naïve lobbying for Anglo-American friendship. It calls into question the attempts to rationalise sensorially intangible phenomena and the impenetrableness of thinking in strictly legislative terms (love above the law). Thanks also (and literally) to the unwillingness to see matters of life and death in black and white, the validity of its humanistic message did not expire with the end of the Second World War. It is not made clear whether Peter’s visions are “real” or whether everything is taking place only in his wounded brain. Though the doctor is presented as a sceptic when it comes to phenomena that we cannot scientifically document, he is given the privilege of being the protagonist’s advocate in his dispute with death. The film is similarly ambiguous in its approach to traditions. Clinging to them hinders development (more precisely, it hinders love), but the ideas of great men are nevertheless used in the trial to demonstrate the maturity of a civilisation standing on a very solid cultural foundation. However, Stairway to Heaven is rightly appreciated primarily for its work with colour and space, which gives an abstract, slightly fairy-tale impression even on earth (the futurological design of the other world, in the spirit of Lang’s Metropolis, conversely evokes scientific starkness, which is further reinforced by numerous symmetrical compositions). The colours of the scenes tell us in advance the spirit in which the following minutes will pass. The red in the opening scene indicates not only danger, but also the budding romance between Peter and June (her deep-red lips are a reminder of the dominant colour of this scene later in the film). The yellow after the first awakening on earth may signify Peter’s uncertainty as to where he is, but also his newly charged life energy (the colour of the sun). The subsequent romantic scene is set among green plants with bold pink and red flowers – the lovers find themselves in a fairy tale or perhaps even in paradise. The scenes with natural colours and without one dominant hue are filled with an attempt to scientifically explain what happened to Peter. The sterile white of the hospital works similarly. Later, in the scene from the doctor’s house, the meaning of green (represented by the ping-pong table and the plants above it, as well as Philidor’s dress) changes. It is the colour of something unnatural (poisonous) that threatens Peter’s life. Besides taking care to ensure that unwanted colours do not interfere with their shots, Powell and Pressburger (and cinematographer Jack Cardiff) also humorously play with the transitions between colour and black-and-white, which serve as a self-referential visual metaphor for other transitions (between life and death, American and British culture, the rational and the paranormal). In any case, it is a picture of many colours. In more senses than you would probably expect from a sixty-year-old fantasy. 85%

Ystävykset (1943)

I can’t entirely come to terms with the fact that this chronicle of one life only veils its war-propagandistic message – the mythologising of the British army – with a boldly humanistic message of friendship between nations (the same idea on which Stairway to Heaven is based). The jovial Clive Candy, convincingly portrayed by one actor in all three acts, personifies everything good about the British Empire, a tradition that all young whippersnappers should revere. He is the bearer of qualities such as loyalty, leniency and love of country (the endlessly mentioned home). The music of his life is a military march. Each of his gestures and everything he says presents an argument for the existence of the army. Fortunately, Powell and Pressburger were clever and capable enough as filmmakers to stick with forming an idealised image of a man who may easily have been modelled on Winston Churchill (who hated the film because of its sympathetic portrayal of the Germans). Above all, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is an exquisite example of how to engagingly chart two human lives over the course of forty years. With the storytelling confidence of New Wave filmmakers, the duo employ original narrative shortcuts (resolving multi-year transitions, omitting important events, condensing time) and audacious Buñuel-esque tests of the viewer’s attention (the three different characters played by Deborah Kerr). The flashback structure of the narrative, where the whole film is an explanation of what happens in the prologue and the individual sequences are similarly based on the explanation of the information provided (the narrative thus atypically moves from effects to causes at both the lower and higher levels), stimulates our curiosity while also functioning as a formalistic expression of the film’s central idea. It is always good to know the context and the origin of current events and thus avoid any possible misunderstandings. Wars are also interpreted as a product of misunderstanding, at least from a female standpoint, the consideration of which is evidence of the filmmakers’ effort to confront different perspectives, all of which in the end, however, confirm the inevitability of a difficult defence. Ideological unambiguity simply belongs to national epics. Let’s enjoy the fact that this one is told with the elegance of real masters. 80%

Padesátka (2015)

Thank God for the youngbloods of Czech cinema, who are not afraid to go beyond the boundaries of good taste, to break with narrative conventions and to step out of restrictive genre pigeonholes. Kotek’s way of telling a story does not in any way conceal the fact that Chasing Fifty is based on a stage play of the same name. He goes against the trend of increasingly frenetic entertainment, instead basing most of the film on a conversation between three men in a single mountain cottage. We learn everything we need to know from the words that we hear. Vilma Cibulková’s parallel trip to the aforementioned cottage ingeniously raises the false expectation that the two storylines will be more tightly intertwined and continuously complement each other. Instead, they come together only at the end, so that the individual stages of the woman’s journey end up being only distracting red herrings. Similarly, the flashbacks – in which there are very unconventional (almost avant-garde) temporal relationships – do not coalesce into a coherent whole, but serve mainly as a redundant illustration of what we hear. This is an inspiring example of hypermediation, in which the old medium does not merge with the new, but comes to the fore (theatrical rigidity, a transparent attempt to keep the characters in an enclosed space for as long as possible, the doubling of a single message by depicting it in both words and images). The film’s creators take an obliging approach to the scattered attention of television viewers by giving preference to a sitcom-style plot composed of loosely connected gags over a more cohesive causal interconnectedness. Thanks to its disregard for narrative logic and rejection of any consistency in the characters’ actions, the film is enjoyably unpredictable. Another unexpected aspect is the abrupt changes in tone along the lines of the “anything goes” approach of modern eclectic artists. The filmmakers are not afraid to cross the high with the low, laughter with tears, blood with semen. Humorous scenes reminiscent of animated slapstick – including the Mickey Mousing that another progressive Czech filmmaker, Zdeněk Troška, likes to use – are juxtaposed with, for example, a scene in which one of the characters has his skull punctured and his leg stabbed (so badly that he loses it). Kotek and Koleček also refused to give in to the unwritten demand for a more sensitive portrayal of a bygone era that would not turn normalisation into an ostalgic open-air museum of crazy hairstyles, knitted sweaters, tight trousers and Polish condom vending machines. For them, the Communist era is only about the surface, because dealing with politics in the post-modern era without grand narratives is passé anyway. The playful caricature of normalisation corresponds to the film’s concept of itself as a self-assured generational manifesto that ridicules the past regime and adults – the older characters are either hysterical and clumsy (Kateřina), pedantic, heartless and inconsiderate (Pavko) or an outright psychopath who “reads” animal entrails instead of newspapers (Kuna). Both the younger and older characters are defined by a single characteristic, in that they are one-dimensional types, which fits well with the exaggeratedly comedic tone of some scenes and contrasts nicely with the attempt at nostalgically touching tragedy found in other scenes. However, I consider the film’s consistent antifeminism to be its most daring departure from the dominant current of contemporary genre cinema. Chasing Fifty is subversive in its conservative chauvinism, its guyish “highlander” humour about women, homosexuals (who drink cranberry juice) and the disabled. There is not a single positive, let alone active female character who acts of her own accord (rather than out of a desire to please men). Rather, the women in the film are lustful sexualised objects who can be happy that someone wants to have sex with them (and thus drive their sadness out of their bodies). In the deluge of films celebrating the awakening of female power, this is truly very refreshing. I look forward to seeing what the promising screenwriter, who has previously shown an extraordinary understanding of the female spirit (Icing), will surprise us with next. I am equally curious as to how Kotek will further develop the humorous motifs from the film that made him an idle to teenage girls (in comparison with Snowboarders, Chasing Fifty is different in that, for example, sex sometimes leads to the conception of a child, so the characters don’t just figure out who slept with whom, but also who is whose son/father/brother).

Jeanne Dielman (1975)

Every neorealist’s dream come true. Even though there is always something happening in this film (cooking, cleaning, setting the table, knitting), it lacks a dramatic plot in the usual sense of the word. It is neither action- nor goal-oriented, nor does it contain any external conflicts. It is more or less composed of scenes “between events”, which would have been cut from a standard narrative film. With hypnotic cyclicality, the same actions are repeated again and again. The concept of space and time is also subordinated to them. The shots are mostly as long as the duration of Jeanne’s activities. She sets the film’s rhythm. The enclosed space-time of the household is an extension of her personality, which, unlike the male protagonists, she does not try to overcome and destroy, but conversely embraces with masochistic humility. Though the interchangeability of the individual days reinforces our conviction that nothing will ultimately happen, when we grasp Jeanne Dielman from the opposite end, we can watch it a second time as a film in which pressure builds up for three hours and will have to be released in some way. It is necessary to understand the radical final gesture from the perspective of the second wave of feminism, which perceives the body as a weapon, identifying the personal with the political. In other words, we shouldn’t consider Jeanne’s action as mere evidence that she has been pulled out of the cyclically repetitive housework. The minimalistic style of frontally shot, symmetrically composed, long and static shots, empty monologues (which primarily have a rhythmic function, as they do not communicate much through their content) and mise-en-scène, in which the slightest change plays a role, does not serve to tell a story with spiritual reach, unlike the films of Bresson and Dreyer. Spiritual reach is exactly what is missing in Jeanne Dielman’s life. While she finds the daily routine stultifying, the film takes on a hypnotic quality thanks to its unchanging rhythm and shot compositions, whose balance reflects Jeanne’s obsessive need for order. We gradually begin to notice the colours, the lighting, the interplay of horizontal and vertical lines and the placement of objects in the shots. Every movement and every change of angle takes on meaning. The director thus does not have to draw our attention to changes through editing or dramatic music. Every disturbance of order becomes exciting in a space with similarly rigid rules and the most gripping scene in the film may be the one in which we wait to see whether the milk bottle whose stability has been disrupted will tip over and spill. Similarly fragile stability and the need to disrupt it are thematised on another level throughout the film, which is worth as much as several feminist essays. 90%

Mediterranea (2015)

In its attempt to offer the first-hand experience of a refugee, Mediterranea is relatively successful thanks to the narrowing of the narrative perspective to the protagonist (which, in addition to the point-of-view shots and spontaneously reacting camera, is carried out by using a shallow depth of field). In addition to that, the alternating locations and imaginative work with sound (and silence) give the film a relatively brisk pace and a steady rhythm. However, the limited supply of information and the effort to be obliging toward the viewer take their toll in the form of a number of simplifications, unoriginality and the absence of a broader context, which I consider to be crucial in the thematisation of migration today. Despite the final explosion of violence (reminiscent of the conclusion of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing), which is of course immediately relativised by the even more brutal violence of the other side (the other transgressions of the refugees are also justified with a similar overlap of one evil with the worse evil of the previous one), it is a one-sided and black-and-white perspective with characters who are either good or bad at their core. On the one hand, this is an extremely important film that transforms fragmentary media reports into a coherent and engaging narrative, though on the other hand it could have exactly the opposite effect than the filmmakers intended due to its blatant manipulation of the viewer and leaving minimum room for discussion. 60%

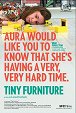

Tiny Furniture (2010)

A comedy of embarrassment. Aura attempts to establish a dialogue with a home that she no longer understands, but which she cannot exist without. She doesn’t know how to set down roots in the unexplored world of people who have graduated from university. She needs to know that she belongs somewhere and that somebody wants her. Throughout the film, she tries to reclaim her position as a daughter, to get permission from her mother to sleep in her bed, to be her child again. At least for a moment. This is not only a manifestation of fear of responsibility and emotional insecurity on her part, but also of dependency, her inability to look past her own problems and see those of others, and the need for someone to guide her. If I can judge from my experience as a viewer, for a person of the same age and with the same starting position as Aura, Tiny Furniture is simultaneously pleasant and annoying. It’s pleasant because it is easy to settle into its microcosm of awkward silences, timidity and impropriety, and it’s annoying because it confronts her with her own immaturity, parasitising on others’ success and constantly looking for ways to make her life easier. But what are we actually entitled to at our age and in our position? Why do we consider it unacceptable to be lonely, without power and without money? The unteachable, negative and self-absorbed characters are both role models and cautionary examples. Lena Dunham shows the naked truth (though still not as “naked” as in the later Girls) without moralising, but at the same time without any romcom refinement. She shows real people whose contradictory characters cannot be judged and condemned in a single sentence. The camerawork is equally expressive and even more ambiguous, as it succeeds in capturing the characters’ mood and situation through the composition of the shots and the involvement of the mise-en-scène (the coldly elegant framing of the apartment as several aseptic cubicles with none of the warmth of home). If you don’t feel embarrassed because of the characters, the environment in which they live will reliably give you the feeling of impropriety. 85%

Blood Simple (1984)

When things go wrong... In a brutally straightforward way, the characters in Blood Simple come to the realisation that infidelity doesn’t pay and that problems with communication can have fatal consequences. The Coen brothers gnawed the conventions of film noir down to the marrow. They don’t spend a lot of time on setting up the plot or introducing the characters, about whom we know nothing except their names (and that Ray served in the military, which corresponds to his way of thinking). Thanks to this, the narrative, which is conveyed with the simplicity of an urban legend that people discuss among themselves, is open to a broad range of interpretations and, at the most basic level, we can enjoy how the film keeps us in suspense without having to deal with the psychology and social backgrounds of the helpless characters hounded by fate. Though this is a run-of-the-mill story of infidelity and revenge, it holds our attention not only thanks to its unique formalistic elements (camera approaches, unusual angles, work with depth of field), but also due to the fact that events develop in ways that are far from what we expect. Some twists come sooner than we would expect, while others don’t happen at all (a forgotten lighter doesn’t play the anticipated role) and events have very unexpected consequences due to the characters being uninformed (one could write long narrative analyses about the masterful creation of a plot based on what a character knows or thinks he knows). Despite its seeming simplicity, Blood Simple is an intoxicatingly well-thought-out thriller for knowledgeable viewers, who will appreciate the fact that the filmmakers don’t try to pull them out of the concept with cheap tricks. Instead of that, they opt for unexpected changes of mood (the bizarre dialogue about Marty’s anal-retentive nature, gleefully dark humour) and scenes that are suspenseful due to their duration (and the resulting anticipation of when “it” will happen) and end abruptly with an economical cut that smoothly transports us through time and space. Not only rhythmically balanced, original and unpredictable in its creation of tension, Blood Simple is an example of a mature debut by filmmakers who know what they want. The Coen brothers’ subsequent genre revisions, though funnier and more sophisticated in terms of narrative, are not as brutally simple in their logic or as cathartic in their simplicity. 85%