Arvostelut (863)

Tappava yhteys (1985)

Only at Cannon Films could Tobe Hooper get a three-picture deal and, what’s more, funding for a bizarre, big-budget project that combines the style of the classic British sci-fi horror movies Quatermass and the Pit and The Day of the Triffids with spectacular special effects and grandiose sets. Though the result ranked among infamous flops and foreshadowed Cannon Films’ financial demise in the second half of the 1980s, its tremendous charm cannot be denied. For its time, it was actually an utterly unique fanboy project in which Hooper enjoyed paying homage to his favourite old-school movies. Like those earlier works, the foundations of Lifeforce are composed of dialogue passages and talking heads. However, these attributes cause it to fail as a spectacle, so it remains merely a tribute for a knowledgeable audience. The colossal deep-space sequences, the apocalyptic destruction of London and the bizarre premise of a nude space vampiress sucking the life force out of men do not in any way change that.

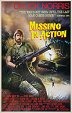

Suoraa toimintaa (1984)

Chuck Norris’s first movie released by Cannon Films pushed his career in a completely unexpected direction. Suddenly, the C-list tough guy became a box-office star and, furthermore, the personification of conservative Republican values reflecting the political atmosphere of Reagan’s America. Cannon Films obviously launched the Missing in Action franchise to piggy-back on the success of the first Rambo flick, but the Stallone franchise was surprisingly surpassed when it came to the shift brought about by Rambo II. It is possible that Missing in Action also drew inspiration from the relatively successful Uncommon Valor released a year earlier, which was the first film to address the issue of American prisoners of war held in Vietnamese camps long after the war ended. On the ideological level, however, Missing in Action differs significantly from both of the aforementioned films. Though it is often overlooked, at its core Rambo II redresses the American defeat in Vietnam, but it does so in spite of the interests of politicians and commanders, just as the protagonists of Uncommon Valor act on their own despite the interests of politicians. Conversely Chuck’s hero does not stand in opposition to the official structures of the US. In Missing in Action, the liars are exclusively the Vietnamese leaders, who use the foreign liberal media for propaganda purposes. As a radical Republican, Chuck did not question his government’s line in the slightest. Accordingly, the film is a one-sided agit-prop pamphlet, which, in contrast to the escalating drama of Uncommon Valor and the superb action of Rambo II, offers only a second-rate action spectacle without any bold staging or choreography.

Imperiumin vastaisku (1980)

The Empire Strikes Back establishes the central paradox of Star Wars fandom – its qualities are predominantly not the work of George Lucas, so the instalment that is adored by all and to a great extent defines the franchise is paradoxically an anomaly within the saga. The first Star Wars laid out the world of a galaxy far, far away and, as an update of old naïve sci-fi adventures in the mould of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, was intended to be a spectacle for children. Thanks to that, Lucas was able to make money from merchandising, which at the time was not yet targeted at the fat wallets of fans, but only family budgets. With The Empire Strikes Back, the franchise was catapulted to cult status in the sense of lifestyle. With its adult conflicts, tense emotions and brilliant dramaturgical structure, the second (now fifth) part of the saga resonated with both teenagers and older viewers. But instead of the father of the franchise, George Lucas, the director’s chair was occupied by his film-school instructor, Irvin Kershner, who had accepted Lucas’s offer under the condition that he could give depth to the story and develop the characters. The Empire Strikes Back is thus closer to fan fiction than to Lucas’s style of light-hearted space operas, which returned in the aspects of Return of the Jedi that were condemned by fans. Like the fan fiction that it in many respects inspired, the second/fifth episode retains Lucas’s worlds, settings, characters and basic motifs, but sets them in a stylistically completely different narrative that dispenses with naïveté, playfulness and melodrama in favour of pathos, fatefulness, intense emotions, twists and dramatic situations with a burdensome impact on the characters. Though the key twists and revelations were devised by Lucas, Kershner’s direction gives them their proper form – it suffices to compare the concept of key scenes and the direction of the actors here with the predominating swagger and inconsistent drama of the other two parts of the original trilogy. The same is true in the case of the film’s other strengths, particularly the brilliant narrative, which, instead of the linearity of the first film, offers the dramaturgically refined alternation of two parallel storylines, which is precisely timed so that the narrative never loses momentum. Together with director Richard Marquand, Lucas tried to emulate this in the last film, but the absence of dramaturgical feel and the preference for adventure attractions led to scenes that are desperately drawn out beyond the bounds of what is tolerable. In accordance with the consensus, The Empire Strikes Back is thus indeed the best episode of the saga, but it does not represent the desired culmination of style, trends and motifs, but rather a deviation or paraphrase that unfortunately reveals the saga’s potential, which remained unexploited in the other episodes. The fact that Lucas entrusted the directing to a filmmaker with ambitions and filmmaking qualities that surpassed his own is actually the cruellest of his notoriously ambiguous decisions. In the area of special effects, Lucas came into his own with The Empire Strikes Back, and the progress made in the three years since the first film, which is noticeable in every trick shot, is truly breath-taking. Lucas later diminished his contribution by releasing a special edition with added digital effects that gave the entire trilogy a uniform appearance. Much thanks and appreciation belong to the fan restoration project of the despecialised edition under Harmy’s direction, which allows us to again marvel at the original form of all three episodes.

Vaarallinen tehtävä II (2000)

Thanks to the fact that the Mission: Impossible franchise changes the director with every instalment, it retains not only its freshness, but also its connection to the current trends in Hollywood cinema. None of the directors works in isolation, as each of them fits into a particular period of Hollywood cinema. Whereas the franchise began to significantly foreshadow trends starting with the third film, M:I-2 now seems like a bitter relic of the decade that it capped off. The revisionism in which a Bond-esque hero falls in love is reduced, with typical ’90s overdone cool machismo, to a ridiculous fairy tale about love at first superficial sight. John Woo's excessively theatrical and gracefully formalistic style is freed from the charged fatefulness of archetypal values and urgency of his Hong Kong films of the time and becomes an unintentionally humorous quirk. It would be nice to celebrate the stylistic freedom and formalism that replace symbolism and formulas, but due to the combination of those attributes with the intrusive dickishness of most of the characters, the film leaves a rather bitter aftertaste. The attempt to make Ethan Hunt an icon of coolness further fails thanks to the futile screenplay, exaggeration to the point of parody, and the cartoonishly overwrought antagonist with perhaps the least charisma ever seen in a movie. Mission: Impossible II is now a frightening reminder of how desperately formulaic and self-regardingly bombastic Hollywood blockbusters were until relatively recently. Not that there aren’t still devotees of the tendency to make dickishness a priority in the 1990s or that today’s sophistication doesn’t frequently slide into self-centred masturbation, but Hollywood’s flagship films are now navigating different waters. After all, the latest instalment of the franchise, Rogue Nation, exhibits a number of parallels with M:I-2, particularly the “bold” villain and the protagonist’s relationship with his ambivalent female colleague. Thanks to the consistent rejection of the superficial and, conversely, the consistent development of the character, as well as the screenplay, which carefully straddles the line between fatefulness and dashing humour, it avoids all of the ridiculous ills of the era when women automatically fell into the arms of the protagonists and the heroes fought angry retributive duels with evil villains.

Berry Gordy's the Last Dragon (1985)

It is difficult to imagine a more delirious pastiche than The Last Dragon, a film in which a youthful martial-arts movie in the mould of The Karate Kid comes together with a 1980s TV variety show, sitcom caricature, blaxploitation, new-age mysticism, cartoonish bad guys, a Bruce Lee monument and the style of early MTV. Surprisingly, however, all of these disparate elements fit together, though the intended result is deliberately less than serious. Thanks to exaggeration and the willingness to constantly take the piss out of itself, the film surpasses seriously intended yet ridiculously cringe-inducing guilty pleasures such as No Retreat, No Surrender and The Karate Kid. The protagonist here is a real martial-arts champion, unlike the whippersnappers who are barely able to stand on one leg. Though The Last Dragon makes fun of the clichés of martial-arts movies and their esoteric pearls of wisdom, it also rather sincerely highlights the benefits of martial arts and pays homage to Bruce Lee. We can find the roots of this notable approach in the martial-arts blaxploitation films starring Jim Kelly, which also often abound with genre excess, but at the same time were based on the perception of martial arts as a way to defend one’s rights and a means to win respect and to assert one’s emancipation. After all, it was due to these values that Bruce Lee became a major icon of African-Americans’ struggle for equality. The Last Dragon actually represents a unique comingling of two diametrically different positions of African-American parallel pop culture – the trash genre movies of the 1970s and the mainstream sitcoms and comedies of the 1980s. Thanks to that, an idealistic martial-arts master, his brother, who still has milk running down his chin and is already spouting ultra-macho lines, a stunningly beautiful music-show host longing for love, and a comically affected bad guy called the Shogun of Harlem with his posse of punks can appear side by side in the same film. And that’s not even to mention the parallel storyline with the evil white magnate who characteristically has no taste in music, and his protégé bimbo mistress, who, like all white people, has no rhythm and performs terrifying song-and-dance routines. It is not in any way surprising that the project was backed by the influential African-American music label Motown, which had previously produced The Wiz, a black variation on The Wizard of Oz.

Double Dragon (1994)

Despite popular prejudice, the 1980s were not the worst era in terms of fashion, style, taste and pop culture. Actually, all of the evil of the ’80s culminated in the first half of the following decade and Double Dragon ranks among the showpieces of that era characterised by hypertrophied campiness. At the same time, the early nineties was the opening chapter in Hollywood’s attempts to systematically adapt pop-culture brands such as comic books and video games. Unlike the current meticulously reverent flattering of fanboys with knowing sophistication and impassioned seriousness, the adaptations back then were rather loosely conceived and wagered on the contemporary style of films for youths instead of taking the source works into account. This tendency apparently arose from 1980s animated television series for older children, such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, BraveStarr, COPS, Bionic Six, MASK and many others, or perhaps from early 1990s juggernauts such as Street Sharks and Biker Mice from Mars. Franchise movies derived from these shows in the1990s, such as the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles trilogy and a brief series of video-game adaptations comprising Super Mario Bros, Double Dragon and Street Fighter took on a colourful palette, exaggerated expression of the characters and a blend of comic-book fantasy and childish irreverence with a pastiche of interconnectedness with the fashion and pop-culture trends of the day. Like the other two video-game movies mentioned above, Double Dragon is fascinating primarily as an adaptation with a completely original narrative. In fact, all that it has in common with the video game itself is the title and a handful of peripheral elements such as punks, street gangs and two brothers as the main characters. On the other hand, the original video game didn’t have a story. The final form of the movie’s world, characters and story, created solely by the screenwriters, is thus all the more insane. Furthermore, when we take into account that the filmmakers simply needed to make something bearing the same name as a successful video game, the effort to create an expansive fictional world with its own mythology and diverse castes is even more surprising. The result is a phantasmagorical mishmash in which every sequence abounds with colour and affected theatricality, while at the same time possessing opulent sets and countless crazy details that form the atmosphere of the movie’s futuristic, post-apocalyptic world. And that’s not even to mention the magnificent cast, which perhaps couldn’t be any more ’90s. One could assume that the filmmakers initiated the project in light of the announcement of the similarly conceived first video-game movie, namely Super Mario Bros., which promised to be a hit of the new generation that would kick off a gold rush of video-game adaptations. However, it was a colossal flop and Double Dragon met the same fate. Of the creatively boisterous video-game movies, Street Fighter was the best, though a significant part of its box-office success was due to the casting of Jean Claude Van Damme. Conversely, the tremendous receipts brought in by the hopelessly unimaginative Mortal Kombat, which replace the pastiche, exaggeration and childishness of the first three video-game movies with pathos and earnestness, determined the direction that Hollywood would take. How would today’s pop culture look if fanboys hadn’t become arbiters of taste and the raucous creativity in the style of Super Mario Bros. and Double Dragon could have continued, finally free of the anti-aesthetic dead weight of the ’90s?

Ultra Flesh (1980)

Porn flicks by the director Svetlana are characterised by exaggeration and humour, but they mostly stay within the boundaries of rollicking comedies that ridicule the narrative formulas of porn movies or take clichéd fantasies to overwrought extremes. Even in the context of her filmography, however, Ultra Flesh is a madcap romp that has no equal in porn or anywhere else due to its absurdity and bizarreness. The premise of an intergalactic heroine who has to save Earth from an evil alien that has rendered every man in the world impotent through sugar is the motivation behind a sequence of completely unhinged scenes. A porn variety show in which dance and sex acts alternate before the eyes of the American president and his horny wife, a summit meeting that takes place on a racetrack (before the leaders of the US, USSR and China start getting picked on by little boys) and a whole storyline involving an intergalactic heroine with the ability to shoot a laser out of her vagina that causes instant erections are absurd enough, but the duo of mercurial dwarves tops it all. One of them (played by Luis De Jesus, who not only appeared in a number of porn movies, but also wore an Ewok costume in Return of the Jedi) has a field day and the other ruins any scene in which he appears with his affected overacting, deranged costumes and malevolent burlesque etudes. Ultra Flesh thus offers up a phantasmagorical mix of porn, a parody of naïve sci-fi adventure movies and a farce ridiculing government authorities (“When you get your erections back, you can go fuck your countries again.”), as well as mischievous clowning and a freak show (besides the dwarves, we have here a truly colourful gallery of aliens from the intergalactic council and Jamie Gillis with a frightening glued-on biker moustache). And, lo and behold, it’s not only deranged, maniacal and unbelievable, but wildly entertaining in places.

Bolero (1984)

Former Hollywood hunk John Derek gained fame through his marriages to beautiful actresses, whom he directed in joint projects, and as an avid photographer, shooting nude photos of them for men’s luxury magazines. Today, his filmography is best known for the last period of his creative career, after his marriage to the enchanting Bo Derek, who proved to be John’s ideal partner not only on a personal level (his marriage to her lasted the longest), but also in terms of professional collaboration. After various ambitious dramatic films with his previous wives, he and Bo moved on to the production of stylised erotic films, which, together with his photography, made Bo a sex symbol of the decade (more precisely, they lived off and cemented that status, starting with her appearance in 10). Though the films that they made together were unreservedly panned by critics and regularly received Golden Raspberry nominations, they were mostly commercial hits, particularly Tarzan, the Ape Man, which became the fifteenth highest-grossing film of 1981. All of their joint projects can be described as film variations on Derek’s photo layouts for Playboy – superficially attractive, titillatingly erotic and candidly naïve. Thanks to its generous production resources, Bolero was their most ambitious project. Whereas the Dereks had financed their other films themselves, this time they got creative freedom and sufficient financial backing from Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, the heads of Cannon Films, whose portfolio was in several respects well suited by the Dereks’ project – in addition to occasionally producing would-be intelligent erotic films like Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Nana, they also strived to elevate their company’s reputation by financing projects by distinctive filmmakers, with greats such as Altman, Cassavetes, Godard and Konchalovsky at the fore. It is also necessary to mention that Golan evidently had ambitions to have all of the leading major stars of the day and of past decades in the Cannon portfolio, and the Dereks’ projects precisely fulfilled that aim. Like the Dereks’ other films, Bolero became a target of ridicule on the part of critics and disparagement from movie fans. But this is only an indication of misunderstanding, or rather an unwillingness to get on board with the game being played. John Derek’s films with Bo cannot be seen as classics with dramatic arcs, character development and conflicts. Nor are they part of any of the traditional genres. They are admittedly naïve and intentionally formalistic odes to Bo’s natural charm, her body and sensuality, and of no less importance, poetic celebrations of the Dereks’ lifestyle. We can view Bolero as a light-hearted, refreshingly emancipatory and slightly meta creative variation on the erotic stories from the red library. Bo plays a rich young heiress who wants to lose her virginity, but her naïve ideals, nourished by images of masculinity from the early 20th century, end in a mostly unexpected, ridiculous clash with reality when icons of romance novels, such the sheik and the bullfighter, fail to fulfil the heroine’s expectations. Her journey around the world through various beds seems almost like an equivalent of James Bond, except that instead of his serious missions to save the world, in her case it is all about debauched egocentric pleasures. Thus, behind a veil of sincere naïveté and playful casualness, a poem of sensuality in praise of carnality, sexuality and Bo Derek opens up for viewers who are willing to yield to the film’s dubious rationality.

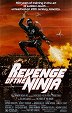

Revenge of the Ninja (1983)

Before Cannon Films found the ideal formula for cheap ninja action movies in the American Ninja franchise, it made a trio of very disparate films. With its box-office success, the first of these, Enter The Ninja, indicated that a boyishly naïve approach to ninjas and a comic-book interpretation of ninja mythology could fill a gap in the market, but Franco Nero, with his futile martial-arts fakery, was not the ideal choice for the lead role. Cannon’s second ninja flick rectified that deficiency by casting Sho Kosugi in the lead role. Kosugi, an actual practitioner of the ninja arts, portrayed the main antagonist in the previous film and had a hand in the choreography of the action scenes. Under his creative direction, Revenge of the Ninja became a unique expat action B-movie in American production. In addition to Kosugi and his son in the lead roles, the cast featured a number of Asian actors who relocated to the US (including, among others, Professor Toru Tanaka). The narrative revolves around the motifs of tradition and roots, which establish a national identity for the hero, who came to America from Japan, while for foreigners they represent only superficial enchantment and a commodity devoid of content. Besides that, Kosugi conceived the film as his own showreel for the purpose of establishing his image as a star. Though he was an actual martial-arts champion, like Bruce Lee he knew that film required spectacle and proper exaggeration more than realistic practical demonstrations. His choreography of the action sequences are in line with this, as it surprisingly has a lot in common with Jackie Chan’s work and even foreshadows Chan’s action films, where he began to systematically cement his image and work on his choreographic trademarks. Kosugi also bases his image on the fact that his hero is not a superhuman fighter, but an ordinary guy who, thanks to martial arts, is nevertheless able to defend his loved ones, even if he himself takes numerous blows in the process. The action is always situated in a distinctive setting whose elements are incorporated into the choreography – most strikingly in this respect is the scene on the children’s playground, which utterly evokes a sequence from Chan’s later Police Story 2. Kosugi also combines fighting with stunts that he performs himself, an approach that Jackie Chan adopted in Project A, which came out later that same year. It is true that Revenge of the Ninja cannot compare to the brilliant work of Jackie Chan and his team of collaborators in terms of the breadth of action, the detailed conceptualisation of the individual phases and the use of settings. On the other hand, Chan had a fundamentally more supportive environment for making his movies, as opposed to the cheap, quickly made flicks from Cannon Films, which raises the question of what kind of performances Kosugi would have achieved if he had had comparable conditions. Unfortunately, Revenge of the Ninja did not become a hit despite Kosugi’s ambition and, in the category of trash C-movies, a highly above-average action sequence, so Cannon Films henceforth always relied on white actors, and Kosugi, after playing a supporting role in the absurd mishmash Ninja III: The Domination, struck out on his own, which enabled him to play bigger roles again, though it further reduced the already low budgets of his films.

Amerikan viimeinen neitsyt (1982)

Lemon Popsicle, a film produced by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus and directed by their devoted collaborator Boaz Davidson, was released in Israeli cinemas in 1978. The film became an international hit and still holds the top spot on the list of most-seen Israeli films, and with its combination of vulgar humour and a serious approach to the problems of adolescence and first love, it laid the foundations for the teen-comedy genre as we know it today. Golan and Globus relocated to Hollywood a year later upon acquiring a majority stake in the failing Cannon Films and while they were looking for new commercially lucrative genres, they hatched a plan to dust off their Israeli hit for the American audience. The Last American Virgin is a literal and, in a number of scenes, even a shot-for-shot identical remake of Lemon Popsicle. Furthermore, it was filmed by the same director. The result is surprising as an odd mix of rollicking sex stories, as if cut out of any given low-grade eighties trash flick aimed at hormonally suppressed youths, which later yields to a dramatic narrative about the burden of unrequited love and even a serious treatise on abortion. In the context of teen comedies about initial sexual experiences, it thus represents a unique ideal that few other contributions to the category have managed to replicate, which, after all, is the reason that The Last American Virgin became a slight generational cult classic in English-speaking countries (much like Lemon Popsicle became in Israel and a number of European countries). Cannon Films tried to continue with the teen-comedy genre for a while, but soon abandoned it. Its superficial and sexually unbridled burlesques Hot Resort and Hot Chili could not compete with the rising trend of intelligent films for adolescents led by the brilliant works of John Hughes and hits with young stars like Tom Cruise and John Cusack.