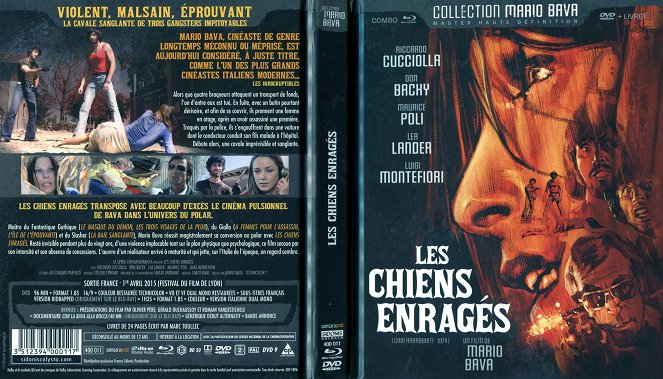

Ohjaus:

Mario BavaKäsikirjoitus:

Alessandro ParenzoSävellys:

Stelvio CiprianiNäyttelijät:

Riccardo Cucciolla, Lea Lander, George Eastman, Maurice Poli, Ettore Manni, Mario Bava, Don Backy, Luigi Antonio Guerra, Emilio BonucciJuonikuvaukset(1)

A gang of thieves hijacks a man's car after botching their getaway from a robbery, taking a woman prisoner along the way. Can the prisoners escape before it's too late? (jakelijan virallinen teksti)

Arvostelut (2)

This film is interesting mainly for two reasons: it’s one of Quentin Tarantino's main sources of inspiration, and then because it’s not at all similar to Mario Bava's previous films, but rather you can feel the influence of his son Lambert. That's why it doesn't play on atmosphere, but rather on the constant fear of death of two kidnapped people, and it's closer to pure exploitation than to the poliziotteschi genre, thanks mainly to the two-meter tall George Eastman's antics (the scene when he forces a woman to urinate standing up in front of the villains is physically unpleasant). There’s no explicit violence except for one single scene, rather psychological terror, stemming from verbal assault and the constant fear of the two kidnapped women that the bandits will later forcibly get rid of them. The fact that the camera does not leave the interior of the car for about seventy per cent of the film's runtime also creates a cramped mood. The final unexpected twist is excellent, but otherwise it does not make a major imprint on the viewer's soul. I like Bava’s previous films better.

()

In light of Bava’s opulent horror operas, the application of a low-budget “carnal” aesthetic (ugly, dirty, evil and in detail) in his first and only thriller is doubly surprising (a more accurate genre classification might be, for example, carjacking poliziottesco). Though Rabid Dogs is often mentioned as a possible source of inspiration for Reservoir Dogs (although it didn’t have its official US premiere until 1998), it seems to have drawn inspiration from American feel-bad movies, particularly The Last House on the Left (a criminal gang with a single rationally thinking member, pissing oneself when under pressure). Bava, however, goes even further than Craven (and even further than he himself went in his giallo) in making it impossible to identify with the victims, most of whom are typically women who most “enjoy” psychological and physical terror. The straightforward linking of needless violence, psychopathic speeches and bizarre dialogue culminates in an extremely cynical twist at the very end (which retrospectively enriches the whole film with additional layers), and a bitter expression of the general mood of society in 1970s Italy. Instead of escalating, the tension is continuously maintained in the claustrophobic space of a single car so that we’re just waiting to see who will do what kind of moronic thing. It is pleasing that this time the “Bava-esque” shot compositions serve not only to please the eye, but also to express the distribution of forces, including hints that even the victims are not completely defenceless. At least in this respect – despite the cheapness of an exploitation flick, the seeming one-dimensionality and the high improbability of some situations (the child not waking up) – this is a more sophisticated film than those that made Bava famous. 70%

()